THE LABOR MARKET IS UNDERGOING CHANGES, especially in information technology, digital marketing, design, and copywriting. More and more professionals prefer flexible forms of employment, while companies increasingly engage external contractors as managed freelance.

However, a controversial model has emerged at the intersection of these trends. Managed freelance involves integrating freelancers into regular workflows without offering them formal employment, social benefits, or guarantees.

This report looks at modern ways people work and the legal differences between them. It also analyzes trends in remote work and project-based jobs. Additionally, it examines the issue of hidden freelancer hiring and its legal effects. Finally, it assesses the impact on professionals. It concludes with recommendations on recognizing such a model and protecting your rights.

Modern Forms of Employment: USA vS Europe

Full-time Employment

Traditional employment is where the worker—an employee—is on the company’s payroll, receiving a salary and benefits. In the U.S., such employees usually work under at-will terms. However, the company can terminate them at any time for any legally permissible reason.

In Europe, employers must justify and provide notice for terminating employment contracts, which enjoy legal protection. Employees receive benefits such as vacation time, sick leave, pension contributions, and other guarantees outlined by law and their contracts.

Contractors

Specialists hired under a fixed-term or project-based contract. Their status may vary. In the U.S., W-2 contract employees—formally employees of an agency or under temporary contracts with limited benefits. They are typical, as are 1099 contractors—independent contractors.

In Europe, labor law governs fixed-term contracts, ensuring that workers typically enjoy nearly the same rights as permanent employees. However, this situation shifts if a contractor registers as a self-employed provider (see below).

Freelancers / Independent Contractors

Self-employed professionals work for clients as external providers. They organize their own work and do not receive benefits from the client, which means they are independent. In the U.S., these individuals work as independent contractors and receive Form 1099 for tax purposes. In Europe, they freelancers or self-employed.

The key criterion is autonomy: a freelancer decides how and when to perform tasks. The client only controls the result. If the company controls what, where, and how the person works, then they are likely an employee. Even if the contract is “freelance.”

Partnership

In the context of individual careers, this is less common but may involve collaboration under profit-sharing terms. For example, a specialist may partner with a project or agency, receiving a share of profits. Legally, a partner is not an employee—a civil law partnership agreement governs relations.

Europe and the U.S., defines partner rights partnership contracts or founding business documents.

Self-Employment

It is a term popular in post-CIS countries, partially analogous to an individual entrepreneur or freelancer. A self-employed person registers their status and pays taxes independently. In the U.S. and Europe, self-employed status means the person works for themselves and can serve multiple clients.

In the EU, recent clarifications highlight that each country sets its own criteria. Typically, you assess levels of subordination and integration. In Germany if a company dictates how someone works, that person qualifies as an employee rather than freelancer. Additionally, following that client’s instructions closely can also be a sign of bogus self-employment. In such cases, the freelancer may be reclassified as an employee with full guarantees.

Legal Differences

The distinction between an employee and an independent contractor is critical in the U.S. and Europe. The U.S. lacks a unified federal criteria list but applies similar approaches. The IRS uses a three-factor test—behavioral control, financial control, and the nature of the relationship. If the client dictates the schedule and work process, provides training, and offers long-term employment, they are effectively an employer. Even with a contractor agreement.

In the EU, countries also analyze the degree of independence. Can workers set their own schedules, take other clients, or hire assistants? For example, the EU Yodel case found that the freedom to choose tasks, delegate work to a subcontractor. A general trend in Europe is the strengthening of gig worker protection.

In December 2024, the EU adopted the Platform Work Directive, introducing a presumption of employment for platform workers. When a platform (or another client) acts like an employer, we will assume the worker is an employee unless proven otherwise.

Status Comparison

The table below summarizes key differences between classic employment and independent freelancing in terms of rights and obligations:

| Criterion | Freelance / Contract | Employment |

| Legal Status | Civil law service agreement (self-employed, individual entrepreneur). Not subject to the client’s internal labor rules. | Employment contract. The employee is integrated into the company structure and subject to internal rules. |

| Control & Management | The contractor plans how and when to do the work; the client controls only the result. For example, the freelancer can work remotely on their own schedule. | Employer can manage the process: give instructions, set a schedule, require attendance at meetings, etc. |

| Exclusivity | Usually, freelancers can work with multiple clients. A lack of strict exclusivity is a sign of independence. | Employees typically work full-time (or part-time) for one employer and can’t work with competitors without permission. |

| Working Hours | Flexible: No fixed hours except for agreed deadlines or calls. Requiring a fixed schedule (e.g., 9–6, 40 hours/week) is a red flag for disguised employment. | Fixed hours or shifts set by the employer. Employees must work specific hours under labor law. |

| Compensation | Paid per invoice or act: by task or hour, as agreed. No vacation/sick pay—only what’s in the contract. | Salary is paid regularly. Plus paid vacation, sick leave, and legal benefits (e.g., minimum wage, overtime). |

| Guarantees | None. No unemployment insurance, employer health coverage, or pension contributions. Freelancer handles taxes and contributions themselves. | Full benefits. Employer provides vacation, maternity leave, insurance (health, pension), and legal/corporate perks. |

| Termination | Defined by service agreement terms. May include contract duration or notice clause (e.g., “10 days’ notice”). Labor law doesn’t apply directly—disputes are handled as contract issues. | Dismissal is regulated by labor law. In Europe, it requires just cause and notice; in the U.S. (at-will states), one can fire without reason, but not for discriminatory motives. Employees may get unemployment benefits or severance. |

Note: The line between formal contractors and employees mainly lies in subordination and integration. If it is a managed freelance many laws may consider them an employee. In such cases, Companies risk reclassifying with tax liabilities, fines, and retroactive employee rights enforcement.

Employment Trends in IT, Marketing, Design, and Copywriting

Growth of Freelancing and Remote Work

In recent years, the number of professionals choosing freelancing or contract work has grown sharply on both sides of the Atlantic. According to a report by Upwork, 38% of the entire U.S. workforce—about 64 million people—freelanced in some form in 2023. That’s 4 million more than the previous year, and the share continues to grow.

Over the past decade, the U.S. freelance economy has steadily added around 1 million people per year over the past decade. European figures are also impressive: Freelancing is the fastest-growing labor market segment in the EU.

The number of freelancers in the European Union increased by 24% from 2009 to 2020, making it the “locomotive” of employment growth. Estimates suggest that about 20 million freelancers are now in Europe, which is ~8.8% of the total workforce. The European Commission forecasts that by 2026, up to 43 million residents in the EU could embrace freelancing as a career choice, indicating significant growth in this area.

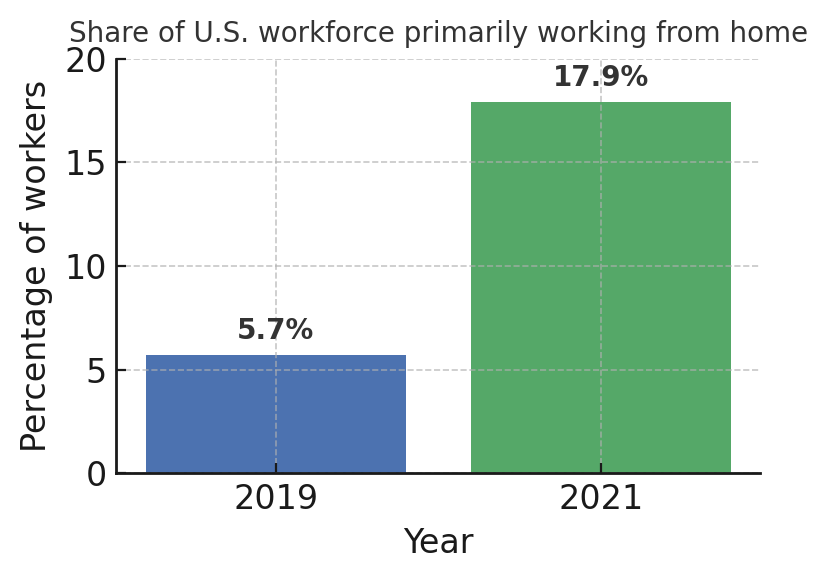

The share of remote workers

Surged during the pandemic. In the U.S., according to the Census Bureau, the proportion of employees working from home rose from 5.7% in 2019 to 17.9% in 2021. The remote format has become standard in many industries.

IT Sector

In information technology, project-based and remote work has long been the norm. Companies hire developers, DevOps engineers, and testers on a contract basis for specific projects. The pandemic accelerated this trend: even large corporations moved to distributed teams. Now, development teams often consist of a mix of in-house employees and external contributors scattered across different countries.

Dedicated platforms for hiring IT freelancers globally (Upwork, Toptal, Gigster, etc.) emerged, enabling companies to find the skills they need regardless of geography. As a result, competition in IT has intensified: on one hand, professionals have more opportunities; on the other, demands for self-discipline and self-management skills have risen.

Marketing and Copywriting

Digital marketing, content management, SMM, and SEO have also massively shifted to outsourcing. Brands often need diverse and unique campaigns, which they can more easily assign to freelance experts. Many marketers and copywriters work as freelance consultants or form agencies. Industry research estimates that up to 70% of content marketers worldwide work remotely or freelance.

The change was partly due to company savings (no fixed costs for permanent employees) and the creative professionals’ flexibility. Online platforms (Textbroker, Contently, etc.) have become significant work sources for copywriters and content writers. However, with the increase in freelancers comes growing competition and pressure on rates—many companies seek to cut costs, sometimes leading to underpricing content services.

Design and Creative Work

The design industry has experienced an actual exodus from offices into freelance freedom. In 2014, only 20% of graphic designers in the U.S. were self-employed. But today, according to Shutterstock, freelancers make up to 90% of those working in design. The rise of online freelance marketplaces drives this transformation, as designers seek to escape routine office work. With the development of remote tools (Figma, Miro, etc.), designers can efficiently collaborate with clients from anywhere in the world.

During the pandemic of 2020–2021, many designers and illustrators who lost office jobs successfully transitioned to remote gigs. The industry has since cemented this trend: for businesses, it’s easier to hire a designer for a specific project (logo, website, ad layouts) than to maintain a full-time creative team. A similar situation exists in adjacent creative professions—animation, video editing, UX/UI design—where freelancers are becoming increasingly dominant.

Distributed Teams

A common denominator across all these fields is remote work. According to statistical agencies, the share of remote workers globally has multiplied since 2020 and remains high. Companies have realized the benefits of distributed teams: access to global talent, savings on office costs, and scalability flexibility.

At the same time, management faces new challenges—overseeing a team where some are full-time and others are contractors. Agile management practices have become widespread, delivering results without strict attendance control.

Many companies now position themselves as remote-first—where office attendance is optional, and even full-time employees can work like freelancers from home. This has become a competitive advantage in the job market for the IT, marketing, and design sectors: the ability to work from anywhere makes vacancies more attractive.

According to surveys, 54% of people would like to work remotely on a permanent basis. Thus, the boundaries between full-time and freelance work are blurring—both technologically and organizationally—laying the groundwork for new employment models, including problematic ones.

The Concept of Managed Freelance and How It Manifests?

What is Managed Freelance?

By managed freelance, we mean a situation where a company hires a specialist as an external contractor (under a service agreement or contract) but, in reality, treats them as a regular employee—imposing corresponding demands and restrictions without providing social guarantees.

In simpler terms, it’s hidden employment: a freelancer’s workday, tasks, and rank often look a lot like those of regular employees. Such relationships often involve misclassification or permatemp arrangements, where employers label a worker as temporary while the role effectively becomes permanent

Signs of Managed Freelance

There are several clear indicators that a freelancer has turned into a “pseudo-employee”:

- Fixed working hours — If an independent contractor must follow a strict schedule, like working 40 hours a week from 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM, this goes against what freelancing means. A key red flag is any job listing marked “freelance” that requires set working hours.

A freelancer should be evaluated based on results, not hours clocked. If the company imposes a time quota, it is likely trying to circumvent labor laws without officially hiring the worker. - Daily control and reporting — In freelancing, the client usually interacts as needed without micromanaging. However, in hidden employment scenarios, they may demand daily reports, participate in calls and team meetings, and assign tasks via internal systems—as they would for employees.

The freelancer is included in internal workflows and managed by a supervisor as if subordinate. For example, mandatory attendance at morning meetings or using corporate email without any “external contractor” label are signs of this situation. - Long-term and exclusive relationship — Freelancing implies the freedom to choose projects. If someone has worked for the same company for years, moving from project to project like a “forever contractor,” it’s likely that the company is intentionally keeping them off the payroll.

A classic example is Microsoft’s “permatemps”—dozens of testers and developers who worked continuously through contracting schemes for 2–3 years. The company used them almost like regular employees but avoided formal employment to save on social taxes and stock options. Eventually, this managed freelance led to a major lawsuit. - Additional duties beyond the contract — Often, once a freelancer becomes attached to a project, the company gradually increases their responsibilities without discussing changes to payment. This is called scope creep, where an external contractor takes on more tasks that resemble a full-time position.

For example, you are hired to create five mockups but it ends up attending all marketing meetings, supervising other designers, and taking on extra tasks—much more than the original project.

A full-time employee could refuse such extras without additional pay, citing their job description, but a freelancer may struggle to defend boundaries if the contract is vague. - No other clients — A freelancer overloaded with work and effectively forbidden (explicitly or due to workload) from taking on other projects becomes a pseudo-employee. In some European countries, it’s explicitly stated that if 80% or more of a freelancer’s income comes from one client, the relationship will likely be recognized as employment.

Having multiple clients is an essential attribute of genuine freelancing. If a company demands exclusivity from a contractor without officially hiring them, it enjoys the benefits of an employee without providing protections.

How Companies Circumvent the Law

The managed freelance model is often used deliberately to cut costs. Companies engage specialists through service contracts or outsourcing firms to avoid hiring them as employees. This allows them to dodge expenses on paid leave, health insurance, social security contributions, etc.

In the U.S., it’s common to hire through staffing agencies or contractor contracts: formally, the person is an employee of the agency or self-employed, but in practice, works for the client company. Legally, the employer is not the end company, so labor laws don’t apply directly.

In Europe, service contracts with individuals or sole proprietors are often used instead of employment contracts. These contracts may contain clauses about “flexible schedules” and “non-exclusivity,” which exist only on paper to create a semblance of independence.

As the UK Supreme Court noted in the Uber case, companies sometimes draft “artificial contracts aimed at depriving workers of basic rights,” and such tricks should not mislead courts. If the actual relationship is clearly one of employment, no wording in the contract can save the company from liability.

Why Do Freelancers Agree to Managed Freelance?

At first glance, a freelancer can walk away if the terms are unsatisfactory. However, specialists often agree to such arrangements for several reasons: the need for income, lack of alternatives, and promises of future employment. Beginners might not identify exploitative setups; they may perceive these situations as the norm for freelancing.

For instance, a recent graduate who lands a remote “content manager” job with fixed hours may not realize that, by definition, freelancers set their own schedules. Moreover, clients may manipulate them: “We’re giving you stability and steady projects—why would you need other clients?” or threaten to terminate the collaboration if the freelancer isn’t “loyal.”

As a result, the specialist ends up in a vulnerable position: de facto tied to one employer but without the rights enjoyed by regular employees.

Legal and Ethical Aspects of Managed Freelance

The Line Between Contracting and Employment

Different countries define the boundary between freelancing and employment in various ways, but everywhere, the key factor is the actual behavior of the parties. If a company acts like an employer by giving orders, setting schedules, and controlling the process, then we may need to reconsider the formal status of the worker.

For example, in the U.S., the Department of Labor and tax authorities regularly investigate cases of misclassification—the improper classification of workers as contractors. To determine the degree of control and dependency, several tests apply, including the IRS’s 20-factor test and California’s ABC test.

In the EU, pseudo-self-employment has also attracted close attention. German law explicitly lists the criteria: absence of the worker’s own business infrastructure, working for only one client, following instructions, and integration into the client’s organization—these all indicate that the “freelance” setup is illegal.

In the UK, lawmakers introduced IR35 rules to close loopholes where individuals work through their own companies for a single client but essentially operate as employees. When the control and duties match those of an employee, the contractor’s pay is treated like a salary, and taxes are withheld.

Legal Precedents of Managed Freelance

In recent years, numerous cases have emerged in which freelancers succeeded in having themselves recognized as employees and obtaining the rights they were owed:

Microsoft’s Permatemps (USA)

A classic case from the 1990s: Microsoft extensively used hundreds of long-term contract workers, excluding them from stock options and health insurance available to permanent engineers. A group of these contractors sued, arguing that they were wrongly excluded from benefit programs even though they worked with full-time employees.

The court agreed that, by several criteria, they were common law employees, and Microsoft was forced to pay a large sum. In 2000, the company settled—paying the temporary workers $97 million in compensation. This case became a lesson for many corporations.

Afterward, companies introduced rules limiting the length of contractor engagements (e.g., a maximum of one year) to avoid the creation of “eternal freelancers.” However, the issue hasn’t disappeared.

Uber and Gig Economy Giants

Major court cases have occurred across different countries. After a long legal battle in the UK, the Supreme Court ruled in 2021 that Uber drivers are not independent contractors but “workers” under British law, entitled to minimum wage, paid holidays, and other protections.

The court noted that Uber controls fares, assigns orders, and significantly limits drivers’ freedom—selling them an illusion of flexible scheduling. This decision forced Uber to revise its relationships with tens of thousands of drivers. It became a landmark for the gig economy: “A contract designed to circumvent the law is invalid.”

The Rider Law in Spain (2021)

This law requires delivery couriers (Glovo, Deliveroo, etc.) to be registered as employees. Companies tried to resist but began moving couriers full-time under threat of fines. For example, Glovo (a division of Delivery Hero) announced hiring ~15,000 couriers in Spain, incurring one-time costs of ~€100 million to comply with the law.

Yodel Case (EU)

This case reached the Court of Justice of the EU: a British courier working for Yodel as a self-employed contractor demanded to be recognized as an employee. The EU court analyzed the contract: the courier could refuse orders, hire assistants, and had scheduling flexibility—the court concluded that under such terms, he could be considered an independent contractor.

However, the court also noted that a national court may rule otherwise if such freedoms are illusory in practice. The key point is that the terms on paper must reflect the working relationship. The EU has not adopted a unified criterion for “employee vs. self-employed,” leaving it to member states, but it has emphasized that the rights of all “workers” (in the broad sense) must be respected.

Violated Rights

The “managed freelance” model affects a wide range of labor rights and protections:

- Lack of Social Insurance — A “pseudo-employee” has no paid sick leave, workplace accident insurance, or parental leave. In case of illness or injury, they are left without income or support, whereas a full-time employee would have a right to sick pay. This puts them in a clearly more vulnerable position while saving the company money (which raises ethical concerns).

- No Paid Vacation — Freelancers are not entitled to paid annual leave, so those working for years without being formally employed must work nonstop or forgo income during time off. European laws treat paid leave as a basic worker right—in the Uber and other gig economy rulings, courts directly cited this violation.

- Violation of Work Hour Regulations — Labor laws limit work hours, mandatory breaks, and overtime pay. Freelancers are outside these norms: companies may overload them without compensation or demand night or weekend work under the threat of contract termination.

Overwork, stress, and a disruption of work-life balance result from bypassing occupational health and safety norms. - No Protection from Dismissal — In Europe, employers protect employees from arbitrary dismissal, but they can instantly terminate a freelancer’s contract without explanation or compensation. Companies take advantage of this: an inconvenient or ill freelancer is “not renewed,” whereas a formal procedure would be required for a full-time employee.

As a result, pseudo-employees constantly live under the risk of sudden job loss without severance or unemployment benefits, harming their sense of security. - Restricted Labor Rights — Freelancers cannot form unions on equal terms with employees because, in some jurisdictions, authorities may view freelancer unions as cartels under competition law. They can’t officially file labor complaints for overtime or harassment—formally, they’re “business partners,” not workers.

Hidden employment erodes labor rights within companies because part of the team remains outside the protection system and does not get heard. This is not just a legal issue—it’s an ethical one.

Ethically, the managed freelance model is considered an exploitation of a legal gray area. Companies reap the benefits of labor while avoiding responsibility for the people doing the work. Workers lose stability and dignity.

As the head of the UK App Drivers & Couriers Union said after their victory over Uber:

“Gig companies sell a cruel lie of infinite flexibility and entrepreneurial freedom while there is dependence and manipulation.”

Freelancing is truly valuable for the freedom it offers—but if that freedom is gone, it is simply the absence of protections, which is unjust.

Consequences for Specialists: Instability, Pressure, Burnout

Working in the format of a “freelancer-as-employee,” specialists often face negative consequences for both professional growth and personal well-being:

- Chronic Instability — A person may spend years performing essential work for a company, but their future remains uncertain. Company can terminate the contract at any moment—for example, if management changes or if the project budget gets cut. Without formal employment, there is no income or job security.

Constant feelings of impermanence lead to heightened stress and anxiety. Research shows that job instability correlates with declining mental health and causes depression and emotional burnout. Many “permanent contractors” fear losing their project, forcing them to accept any conditions, overwork, and avoid taking time off. - Lack of Career Growth and Development — Employees on staff can receive promotions, move into more senior roles, and be eligible for company-sponsored training. On the other hand, freelancers often remain on the same level as “external providers” outside the hierarchy of roles.

Companies often appreciate their contractors’ contributions, but they rarely promote them; instead, they hire newcomers at higher-level positions, bypassing the current contractors.

This can hinder professional development. Furthermore, this type of experience doesn’t always look strong on a résumé: years of “project-based” work for a single company without an official title can raise questions from future employers. - Financial Risks and Lack of Benefits — As mentioned earlier, no paid sick leave means illness directly hits the freelancer’s wallet. No paid vacation—you work all year round or save up beforehand. Employers do not make pension contributions, so if the specialist does not save independently, they will not build financial security for the future.

This results in freelancers having a thinner financial safety net than their in-house counterparts. According to surveys, many gig workers don’t even have $400 saved for emergency expenses. Any unforeseen event (illness, drop in orders) can push them to the brink of financial vulnerability. - Overwork and Pressure — Freelancers often work longer hours to stay on a project—without additional pay. Managers may take advantage of this situation by asking employees to put in “a bit more” work in the evenings, as overtime isn’t regulated by law. Over 44% of remote workers in surveys admit they’ve started working more hours than before.

For freelancers, the problem is even worse: they feel obliged to please since contract renewal is at the client’s discretion. This leads to burnout: the cycle of alternating between downtime (stagnation) and overload (stress) creates an unhealthy rhythm.

Researchers have observed a specific phenomenon called “gig stress,” where constant uncertainty about workload—oscillating between feast and famine—negatively impacts mental health more than stable workloads do. - Sense of Injustice and Demotivation — Being “second-class” within a team is psychologically tough. When employees around you receive corporate bonuses, take paid vacations, and attend training. At the same time, the freelancer loses all those perks—despite working just as hard—which breeds discontent and lowers motivation.

Over time, disappointment builds—both in the company and the nature of the work itself. Many talented professionals in such situations either look for better conditions elsewhere or leave the field altogether. This leads to losses for both individuals and the industry: high turnover and missed talent.

It’s worth noting that some people consciously choose to contract for flexibility. However, “managed freelance” kills the main advantages of flexible work—freedom and autonomy. The downsides remain: lack of protection and constant pressure.

This model may offer short-term benefits to businesses, but it lacks sustainability. Burned-out and disillusioned professionals cannot consistently deliver high-quality results over time.

Recommendations: How to Recognize and Protect Your Rights

If you are a specialist in IT, design, marketing, or content and are considering freelance collaboration, it’s crucial to determine whether you’re being led into a trap of hidden employment. Below are tips on how to recognize exploitative models and protect yourself.

How to Recognize a Risky Model?

- Read the terms of the offer carefully

If a job posting or contract labeled “freelance/contract” includes requirements to work full-time, follow internal rules, and be available during strictly set hours, that’s a clear red flag. Be cautious if the client expects you to behave like a staff member without formal employment. - Check the contract wording

A freelance agreement should focus on the deliverable or result (e.g., a specific product or service) and not contain disciplinary clauses. Any mention of a probation period, mandatory personal execution without the right to delegate, or compliance with company rules signals an employment contract disguised as freelance. - Clarify your ability to work with other clients

Ask directly: “Can I take on other projects simultaneously?” If the expectations of full commitment and workload suggest full-time hours, then you should demand corresponding compensation and guarantees. In some countries (e.g., Germany), working exclusively for one client can lead to legal problems for both sides, including fines for bogus contracting. - Research the company’s reputation

Talk to other freelancers and read reviews. If the company frequently hires “eternal juniors on outsourcing” or has faced legal disputes, think twice. Freelance communities (forums, chats) often share blacklists of bad-faith clients. Check if your potential client is there.

How to Secure Your Legal Rights as a Freelancer?

- Put everything in writing

Never rely on verbal promises like “We’ll give you paid vacation later” or “We’ll officially hire you in six months.” Include key terms in the contract: a list of services, work schedule (or a clear statement that you set your own hours), acceptance, and payment procedures. - Draw the line

In communications with managers, assert your status politely but firmly. If someone asks you to take on extra tasks not included in the contract, gently remind them of the agreement:“That’s beyond the scope of my services—let’s discuss a separate contract or an adjustment to the budget.” - Don’t be afraid to say NO to unpaid work

Freelancers have the right to refuse tasks not covered in the agreement. Of course, do it diplomatically. Offer a compromise:“I can take this on, but we’ll need to revisit our agreement and adjust the fee.” - Diversify your client base

The golden rule of freelancing: don’t put all your eggs in one basket. Even if you’re working full-time for a great company, keep some time free for side gigs or personal projects. It’s not just extra income—it’s your safety net. - Stay informed and seek expert advice

Track legal updates for freelancers in your country and your client’s country. For example, if you work for a U.S. company, it helps to understand IRS criteria so you can structure the collaboration to keep both sides safe. - Join forces with peers

Although formal freelancer unions are rare, there are communities and associations of independent workers. They can advise on what to do, share case studies, and even help raise collective demands. Solidarity builds confidence. - And most importantly, remember:

Your skills are valuable, and if one employer tries to exploit you, there will always be another who offers better conditions.

Conclusion

The managed freelance model is a byproduct of our transitional era, where old labor norms haven’t yet caught up with the new digital economy. However, laws and professionals are gradually learning to identify and shut down such schemes.

Companies that want to stay compliant and ethical are also adapting: Some are moving key contractors onto the payroll, and others are offering hybrid options (e.g., paying for insurance even if the person isn’t formally employed).

For professionals, the main advice is this: Value your work and know your rights.

Flexible work can be a blessing—but only if it’s truly flexible, not one-sided.

Demand transparency and respect, and then freelancing can truly become freedom, not a trap.

by